This is highly significant, given that colorectal cancer is the most common cancer in most Western countries, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.

Since then, we have greatly improved the performance of the detection test, by using one that avoids the need for a restrictive diet in the days leading up to the test. Moreover, it is far more sensitive than the initial test, which means that by analysing a single sample, we obtain better results than before, when we had to analyse three samples.

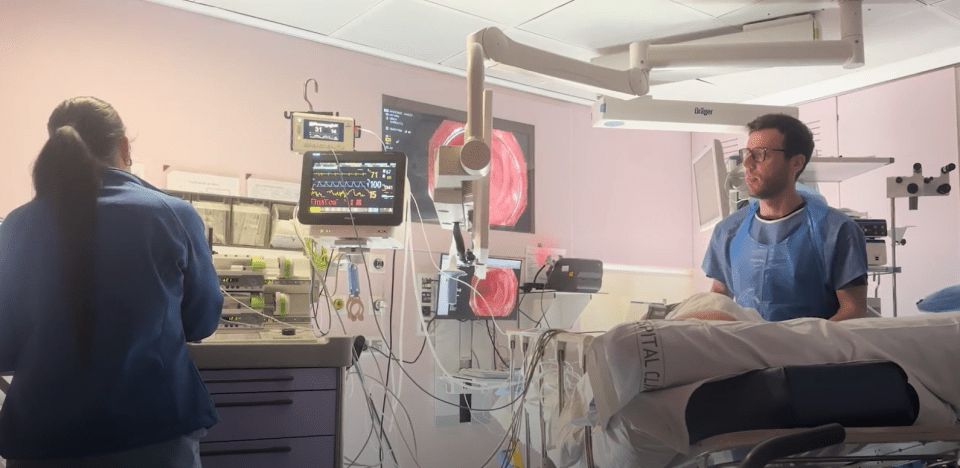

Colorectal cancer screening through faecal occult blood testing is effective

This year, we have taken a further step by demonstrating the screening by faecal occult blood testing achieves the same results in terms of reducing mortality and the incidence of colorectal cancer as a direct colonoscopy, a very common strategy in countries without a public health system, such as the United States. The reason is that the faecal test is more widely accepted by the population, which means greater participation.

Participation in screening programmes is therefore essential to achieving our health objectives. In the case of colorectal cancer, these are to reduce the incidence by identifying precursor lesions—the well-known polyps—and their subsequent removal using endoscopic techniques, and to reduce cancer-related mortality through earlier detection of tumours. The latter not only improves the prognosis for the person suffering from the disease, but also allows for significant savings in the resources used in their treatment, making screening a cost-effective strategy.

Despite the scientific evidence available today to support all of the above, we are unable to exceed a 50% participation rate, whereas breast cancer screening reaches 80% in most countries where it is carried out.

What is preventing participation in colorectal cancer screening from taking off?

We know that women are more receptive to preventive strategies than men, but that does not explain everything. It may be due to apprehension, or fear of the results, but burying our heads in the sand will not prevent cancer. A colonoscopy, which is necessary when the faecal occult blood test result is positive, is an “unpleasant” examination and, in some cases—very few—it can be associated with complications such as perforation or bleeding. Finally, despite being a country with a certain tradition of scatology, obtaining a small stool sample can make us hesitate.

Screening, like vaccinations, is a public health measure that the population must accept freely and voluntarily. Those of use who are dedicated to prevention have a responsibility to inform the public of its benefits—which are many—and its drawbacks—which also exist—with objectivity and transparency, so that citizens understand that they benefit not only themselves but also as a society as a whole, promoting a more equitable distribution of available resources and contributing to the sustainability of the public health system.

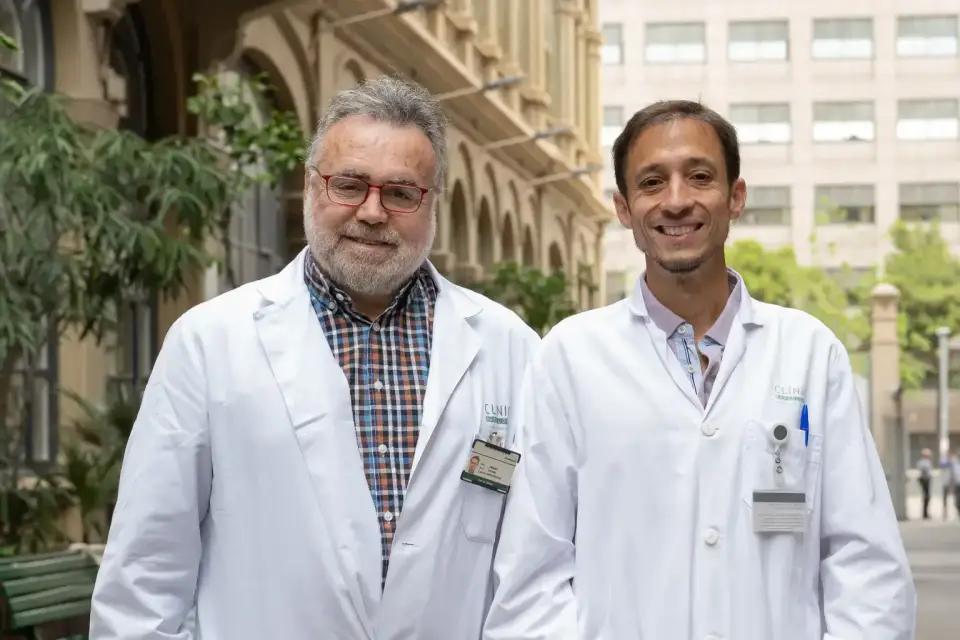

Castells A, Quintero E, Bujanda L, et al. Effect of invitation to colonoscopy versus faecal immunochemical test screening on colorectal cancer mortality (COLONPREV): a pragmatic, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2025; 405: 1231-1239